Thorough Review of U.S. Tariff History: History Will Not Repeat Itself, but It Will Imitate

Is the Trump Administration's Tariff Hike a Stroke of Genius or a Misstep?

Original Article Title: A Tale of Two Tariffs

Original Article Author: Citrini, Analyst

Original Article Translation: Felix, PANews

Impacted by the U.S. tariff escalation, the global economy seems to have entered a state of disarray. Is the Trump administration's tariff imposition a stroke of genius or a misstep? Analyst Citrini, in a post from a historical perspective, reviews past tariff events and gradually analyzes the future economic situation. The following is the full content of the article.

“This might be an erroneous view”

Benjamin Franklin wrote in 1781:

“But I indeed find myself rather inclinable to adopt a more modern sentiment, which is, that every nation seems to be the best trade, that is most open and unrestricted. In general, I only wish to hint, that commerce is the mutual exchange of the necessaries and conveniences of life, and is the more beneficial and thriving, the more free and unencumbered it is, and every country is most happy when in himself.”

Since “Liberation Day” (PANews Note: April 2nd, declared by Trump as "Liberation Day," announcing the global tariff plan), I have spent a week in the United States and a week in China. In both countries, I have spoken with entrepreneurs affected by tariffs.

Whether importers or exporters, enterprises engaged in varying degrees of international trade in these two drastically different regions share a common trait: uncertainty.

Why this uncertainty? A simple fact is that almost everyone has only experienced a world where globalization has constantly increased, trade has been relatively free, and the U.S. has been the world's hegemon and reserve currency.

With this being called into question, investors and operators are clearly seeking frameworks to navigate the future. For systems built on an “instant” basis, “wait and see” is a lethal strategy, but there seems to be no other option.

For instance, in a conversation with a top 100 ranked company in Shanghai (by trade volume), they mentioned: “We should be ramping up for holiday orders right now. But we don’t have a single order yet.” Anyone unfamiliar with how imports work should realize: first, placing orders for an event typically needs to be done 8 months beforehand. Secondly, we are undergoing quite a significant shift.

Chinese companies have generally believed that tariffs are something they can adapt to. In the past, a 10% tariff might lead buyers to seek price cuts from Chinese factories (easily doable). While factories obviously cannot adjust to tariffs of over 100% through price reductions, they did believe they could maintain a cost advantage relative to U.S. domestic manufacturing through such cuts post-tariff. However, all of that is irrelevant when no one is transacting.

It's been over two years since I last published a historical article. These articles may not necessarily be actionable. But this article seems timely. Sometimes, the only way to understand the future is to know the past.

Mercantilism, isolationism, protectionism, and many other -isms have been thrown around haphazardly, but few care about the meanings behind them. While I'm not an economist, I am a fan of economic history. Let's consider this article a popular science piece. This article does not discuss what stocks to trade, nor does it make directional judgments on forex, stocks, or interest rates.

Understanding Tariffs from a Historical Perspective

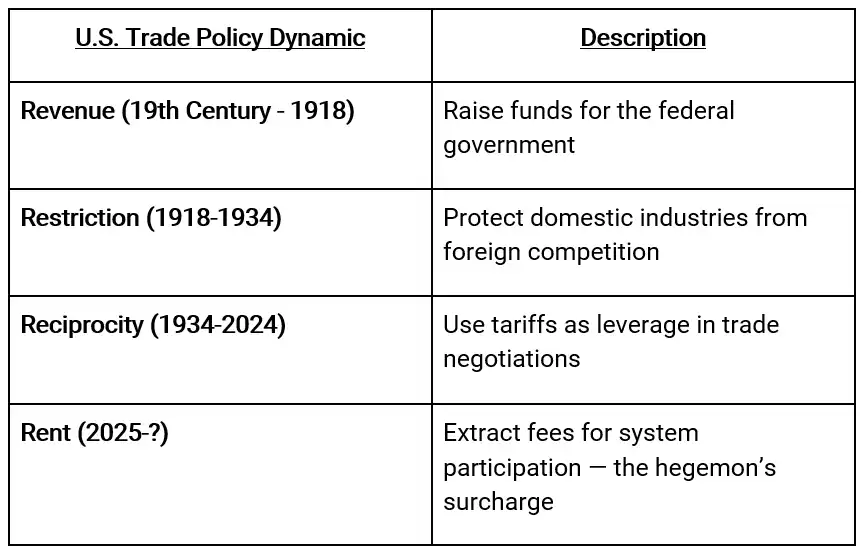

Today, few have truly experienced an economic situation akin to tariff periods of the past. The best work on exploring the history of U.S. tariffs is "Clashing over Commerce," a book I've been rereading for the past few weeks. It is written by Douglas Irwin, a renowned historian of U.S. trade policy and economics, who presents the "3R" framework to understand the political economy of tariffs.

Historically, the "3R" framework of U.S. tariffs:

Revenue

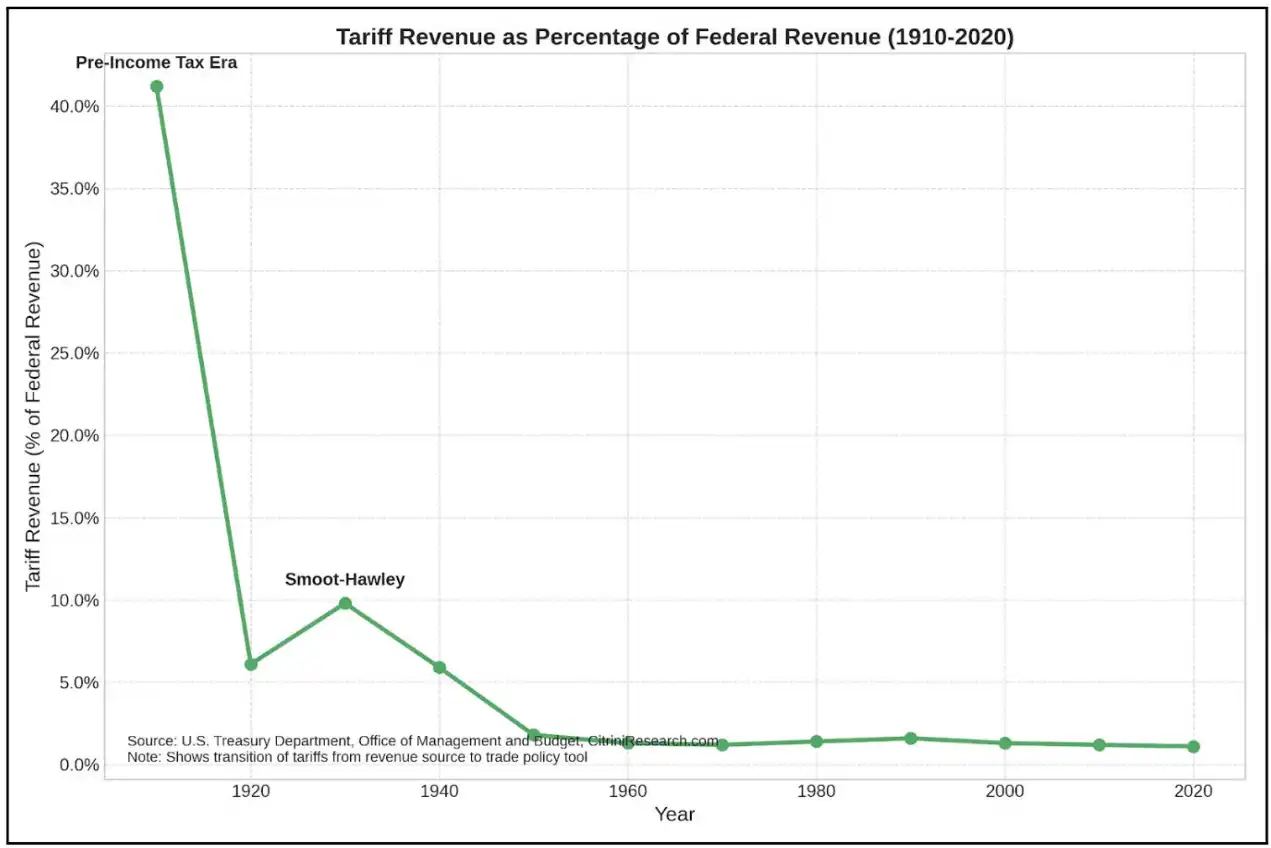

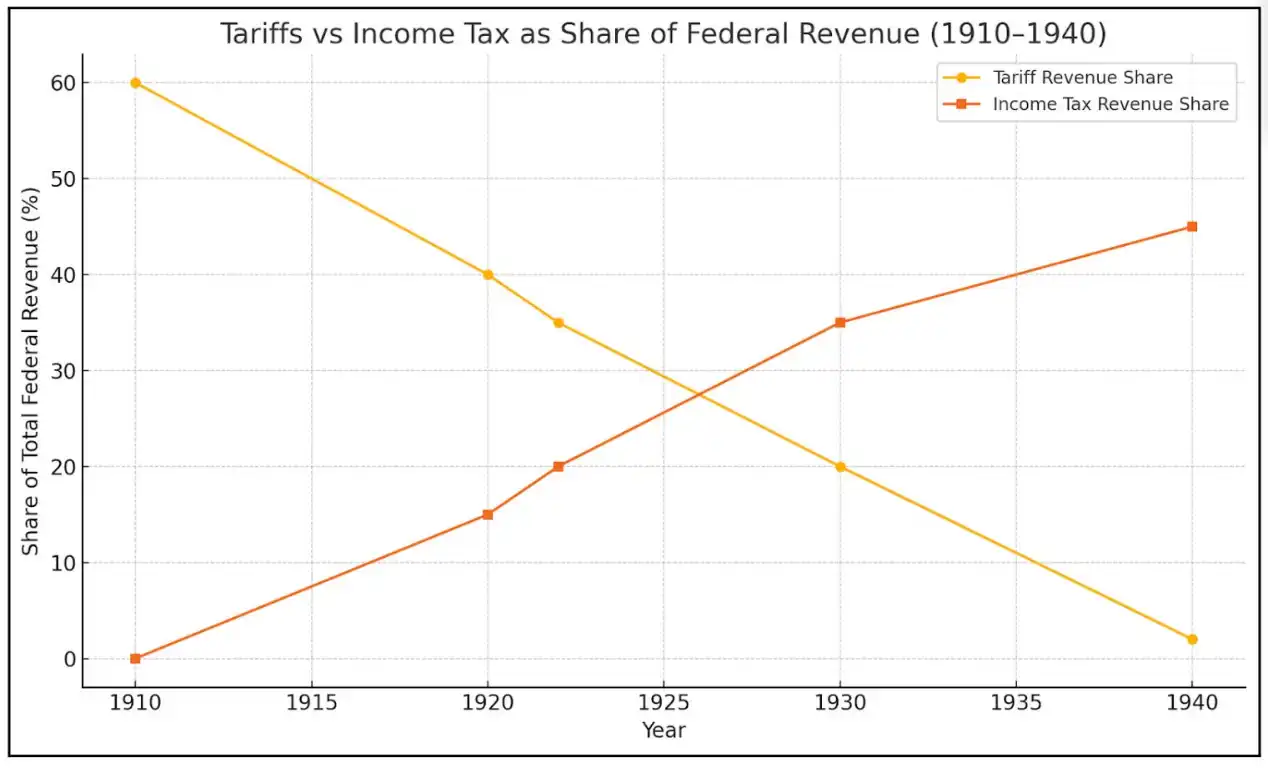

Tariffs were the primary source of government revenue, especially in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tariff acts have long been criticized as opaque and unwieldy policy tools, even though they were the main source of government funds, as depicted in this 1883 political cartoon.

Prior to the establishment of the Internal Revenue Service in the U.S. (1913), there was no income tax. In the 19th century, tariffs accounted for over 90% of government revenue. Back then, tariffs were primarily used to raise revenue rather than for protectionism — seen as a more palatable way to tax the populace without inciting rebellion. For almost a third of the 20th century, less than 15% of U.S. citizens paid income tax. The rest paid invisibly through the prices of imported sugar, timber, and wool. Tariffs were the original hidden tax: collected at the ports, paid at the checkout.

First and foremost, they were a means of funding the state, avoiding the kind of backlash that could come from domestic taxes (a lesson learned from events like the Whiskey Rebellion). In Irwin's narrative, the revenue question dominated the Republic's early trade policy, with even protectionist arguments having to be made through a revenue-first lens.

Restriction

Tariffs protect domestic industries. After World War I, tariffs increasingly became a political tool to cater to domestic industries facing foreign competition — the driver of protectionism. Irwin points out that as the revenue motivation waned (thanks to income tax), the restriction motivation increased. Post-World War I, tariffs increasingly served industry lobbies rather than the Treasury.

Reciprocity

Tariffs have been a bargaining chip in international trade negotiations. By 1934, income tax gradually replaced tariffs as the primary source of federal revenue - the New Deal and World War II accelerated this shift. Tariffs became a bargaining chip in global trade negotiations.

This is exactly the logic behind the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and later the World Trade Organization. The era of reciprocity marked a move towards liberalization, away from isolationism. The hegemonic power (the United States) sought access to foreign markets by lowering tariffs. Tariffs were no longer a barrier but more like a leverage. Voluntary Export Restraints (VERs), which aimed to coerce countries into implementing export restrictions through behind-the-scenes deals, replaced tariffs and were eventually superseded by more extensive and larger-scale free trade agreements. This paved the way for the era of multilateral free trade at the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century.

1922: Fordney-McCumber Tariff

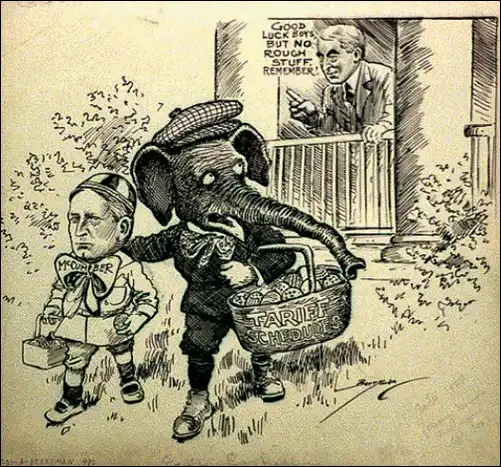

The Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act was a precursor to early protectionist overreach and the first true case of levying tariffs for non-revenue purposes.

Imagine the post-World War I prosperity in the United States: industrial output was high, but farmers were increasingly impoverished. The most concerning issue at the time was cheap competition from Europe. However, Europe owed the United States a lot of money and due to the continuously rising tariffs in the U.S., Europe could not sell anything to the U.S. So, it was obvious that the U.S. raised tariffs again.

In 1921, Congress passed an emergency tariff act, followed by the comprehensive Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act in 1922 signed by President Warren Harding.

This law significantly raised tariffs well above the low levels set by the 1913 Underwood Tariff and higher than tariff levels since the Civil War (although, in terms of tariffs on imported goods, the rates remained roughly the same as the 1909 Payne-Aldrich Tariff). Furthermore, the law granted the President the power to adjust tariff rates by up to 50% to "equalize the cost of production at home and abroad."

What were the results? Urban industries flourished in the 1920s, while agriculture entered a long period of decline, and Europe's trade surplus gradually shrank as they needed this surplus to repay the resources provided by the U.S. during the war.

For the American industrial sector, the 1920s were a decade of prosperity. Between 1922 and 1929, manufacturing output grew by nearly 50%. The unemployment rate dropped from 6.7% in 1922 to 3.2% in 1923. Industries such as steel, chemicals, and automobiles thrived under the protection of tariff barriers. Protected industries expanded, increased their workforce, and became profitable. During this period, business profits almost doubled.

However, the situation was completely different in the agricultural sector. Agricultural income plummeted from $22 billion in 1919 to $13 billion in 1922. While urban areas were booming, the American countryside was plunged into a decade-long Great Depression, a decade ahead of the Great Depression. What was the reason? The European markets were closed due to retaliation, and American farmers who had expanded production during the war faced a sharp drop in demand and prices.

In the 1920s, protectionism brought concentrated benefits. If you were an urban industrial worker, it was a great time. However, if you were a farmer, it was the beginning of 20 years of hardship. The momentum of protectionism had already begun and had achieved some level of success for certain people (although others paid a high price).

1930: The Blunder

High tariffs, great depression.

In 1928, Herbert Hoover was riding high. The great engineer won the presidential election in a landslide victory: securing 444 electoral votes, while Al Smith only got 87, and Hoover even surpassed Warren Harding's county count from 1920, and he won 58% of the popular vote. The "prosperity president" promised in his inaugural address to the American people to "wipe out poverty completely" — however, these words soon turned into his nightmare.

The stock market was soaring, unemployment was low, and Americans were buying cars, radios, and refrigerators at an unprecedented pace. Since McKinley's victory in 1896, the Fourth Party System dominated by Republicans seemed as entrenched as ever.

Like his Republican predecessors, Hoover was a staunch supporter of protective tariffs. Hoover declared during the campaign: "For 70 years, the Republican Party has consistently supported a tariff for full protection of American labor, American industry, and American farms from foreign competition." He made tariff protection, especially for agriculture, the cornerstone of his economic agenda.

As Secretary of Commerce in the Harding and Coolidge administrations, Hoover developed a clear protectionist idea: the United States should essentially limit imports to products that cannot be produced domestically. This was not a radical move but rather the pinnacle of the McKinley Republican tradition, a natural extension of Fourth Party System economic orthodoxy.

Citing the "success" of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act (total U.S. imports had increased since the passage of the act) as evidence, Hoover demonstrated that the United States could protect its domestic industry while expanding sales in Canada. In 1926, he wrote: "Considering the vast outlook of our trade, we may disregard the fear that raising tariffs would drastically reduce our total import figure, thereby destroying the ability of other nations to buy our products." In a campaign speech in 1928, he stated: "To suggest that we cannot have protective tariffs and an expanding foreign trade simultaneously is baseless. Today, we have both."

This was followed by the "Black Thursday" of October 24, 1929, and five days later, "Black Tuesday," when the stock market lost over $30 billion, almost twice the amount the United States had spent during World War I. The roaring '20s came to a sudden halt. Amidst the turmoil, tariff negotiations did not simmer down but instead escalated:

Given the economic shock, Congress not only did not reconsider the tariff legislation but instead doubled down. The initial Agricultural Tariff Act morphed into what is now known as the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, named after its primary sponsors Senator Reed Smoot of Utah and Representative Willis C. Hawley of Oregon. What was originally intended to provide relief to farmers turned into an industrial protectionist monstrosity.

What started as targeted measures to protect American farmers turned into a protectionist free-for-all. During 1929 and early 1930, as the bill made its way through Congress, the number of industries protected grew exponentially. Ultimately, the act raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods, marking the highest tariff rates in U.S. history since the infamous "Tariff of Abominations" in 1828.

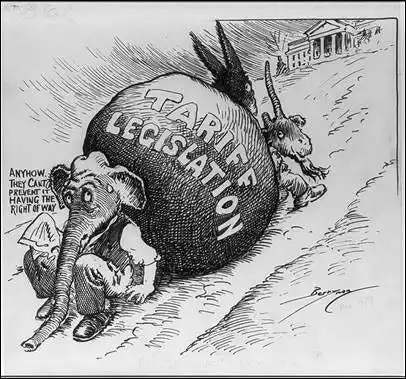

A cartoon depicting a weary Republican elephant sitting in the middle of the road, leaning against a large rock labeled "Tariff Bill"

The market was not convinced. 1,028 economists, despite their ultimate disagreement on how to navigate the economic woes of the Great Depression, found consensus on one point—if the bill were to pass, it would be a disaster.

They wrote a letter to Hoover, pleading for him to veto the bill:

May 8, 1930 Front Page News

Thomas Lamont, a partner at J.P. Morgan, later recalled, "I almost went down on my knees to beg Herbert Hoover to veto the asinine Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act. This act would so alienate the opinion of the world."

Henry Ford spent an entire night at the White House trying to persuade Hoover, arguing that the tariff would cause serious economic harm.

However, on June 17, 1930, Hoover still signed the bill. While political suicide did not happen overnight, this move was sufficient. The unpopularity of the tariff grew rapidly, as evidenced by the frequent reader letters in The New York Times:

The next thing that happened was as they say: over 25 countries took retaliatory actions. Global trade collapsed. In 1929, US imports were $4.4 billion, which dropped to $1.3 billion by 1932. Meanwhile, exports fell from $5.4 billion to $1.6 billion. Between 1929 and 1934, global trade volume decreased by approximately two-thirds.

The stock market crash of 1929 triggered an economic recession, and tariffs turned this recession into the Great Depression. Initially a financial shock, it later evolved into a systemic crisis, as policies—especially the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act—chocked demand from the supply side when it was already declining.

As economists had predicted, American consumers and businesses paid the price. While tariffs may have protected some job opportunities in certain industries, they ended up destroying more jobs by raising the prices of imported raw materials and shutting the door to US export goods in foreign markets.

The Democrats recognized this disaster and made tariff reform a key campaign promise in the 1930 mid-term elections—a move that gave them control of both houses of Congress for the first time since 1918. Referring to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, Roosevelt said, "It forces the various countries of the world to erect such high trade barriers that world trade is declining to practically nil."

The outcome was clear: the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was a complete failure.

How Did the Tariffs of 1922 Differ from Those of 1930?

First, looking at the starting point: the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act was implemented during a period of relative global economic growth, particularly in the US. The roaring '20s masked many of its inefficiencies. In contrast, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was passed after the 1929 stock market crash, by which time global demand was already contracting. It exacerbated an already dire situation. From a protectionist perspective, tariffs acted as a catalyst for economic downturns, but they still needed a trigger.

In 1922, there was high business and consumer confidence, abundant credit funds, and a lenient financial environment. By 1930, bank failures, significant stock market declines, and credit tightening had become commonplace. This was when the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was enacted, significantly raising tariffs, covering as many as 20,000 types of goods. This undoubtedly added insult to injury, indicating that the government had taken a frantic policy at a crucial moment, further panicking investors who feared an escalation of protectionism.

Secondly, Retaliatory Measures. The Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act triggered some limited retaliatory actions (such as the measures taken by France in 1928 and selective tariff imposition by some European countries), but global trade continued to expand in the 1920s. It is easy to measure the damage caused by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in terms of its direct economic impact—raising the average tariff on goods subject to U.S. import duties to 59.1%, the highest level since 1830. However, the real disaster was not the tariff itself, but the global retaliatory actions it sparked.

Canada was the United States' largest trading partner at the time, and had not taken significant retaliatory action against the U.S. for its previous tariff increases. The Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act of 1922 raised tariffs on key Canadian exports such as wheat, cattle, and dairy, but Canadian producers viewed these as merely returning to pre-World War I levels, which they could tolerate.

The situation was different with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. At that time, the global economic recession was worsening, and Canadian exports were already suffering. In July 1930, soon after the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was passed, the Canadian Liberal government was defeated in an election by the Conservative leader Richard Bennett. Bennett fulfilled his campaign promise to "forcefully" open up the world market through tariff increases. By pushing other countries to the brink, their reactions became increasingly unpredictable.

In September 1930, Canada significantly raised tariffs on 16 types of U.S. products, which accounted for about 30% of U.S. exports to Canada. Not stopping there, Canada also negotiated preferential trade agreements with other Commonwealth countries, further eroding the competitiveness of U.S. export products.

The retaliatory actions did not stop at Canada. By 1932, at least 25 countries had taken retaliatory measures against U.S. goods. Spain specifically targeted U.S. cars and tires with the "Wes Tariff." Switzerland boycotted American products. France and Italy imposed quota restrictions on U.S. goods. The UK abandoned its traditional free trade policy and also adopted protectionist measures. This led to a deteriorating situation, with global trade stagnating due to uncertainty and the escalating tit-for-tat trade policies.

Thirdly, Global Financial Conditions. In 1922, the U.S. was still an emerging creditor nation, but the gold standard had not yet been fully restored, and many countries were still recovering from World War I. There was no tightly integrated global financial system at that time. However, by 1930, the gold standard had been reestablished globally. The connections of international trade and debt flows became even closer.

Lastly, from a symbolic perspective, while the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act was a bad policy, it was somewhat expected. Tariffs had been a norm in the U.S. since the Civil War, and many trading partners viewed the Fordney-McCumber Tariff Act as just returning to pre-World War I levels. However, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act was seen as an escalation at a time of global fragility. It indicated a shift for the U.S. towards a more inward-looking economy at a time when it had solidified its position as a creditor nation. It undermined confidence in global coordination and may have prompted many countries to abandon the gold standard shortly thereafter.

Market participants and policymakers interpret the Smoot-Hawley Act not just as a tariff issue, but as a worldview: isolationist, chaotic, and irrational. Uncertainty has stifled business investment.

This was a unique and unprecedented disaster in the era of protectionist trade policy, paving the way for Roosevelt's election. Roosevelt quickly repealed the tariffs and passed the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA).

1934: RTAA—The Beginning of Reciprocity

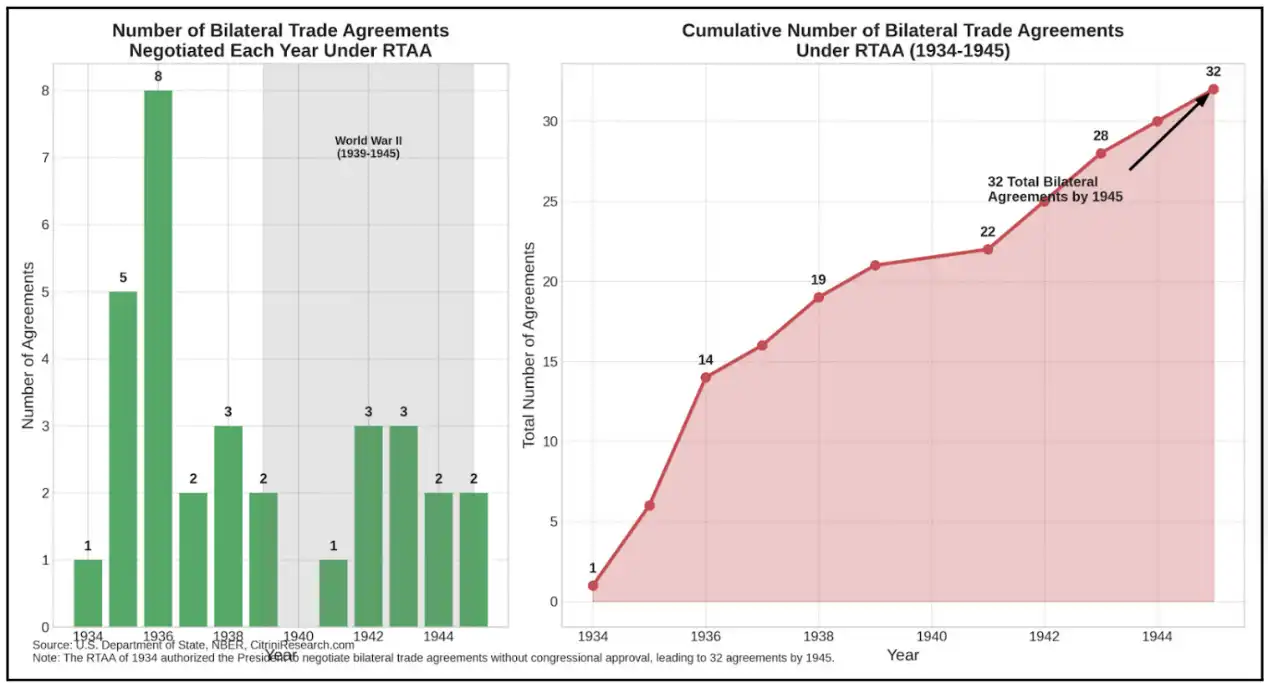

After the protectionist disaster caused by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, U.S. trade policy reached a crossroads. The enactment of the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act in 1934 marked the transfer of power to determine trade policy from Congress to the executive branch, initiating a shift from "restriction" to "reciprocity." This institutional reform fundamentally changed the way trade policy was formulated and laid the foundation for a more liberal trade regime after World War II.

The history of modern international trade began with Cordell Hull, a Democrat from Tennessee who later became the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State. Hull's journey from the agriculturally rich South deeply influenced his views on tariffs and trade. Unlike his Northern colleagues who sought to protect manufacturing, Hull understood that high tariffs would harm agricultural exports.

Signing the "U.S.-Canada Trade Agreement." (Front row, left to right): Cordell Hull, W.L. Mackenzie King, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Washington D.C., U.S.

November 16, 1935

Hull's understanding of trade at the international level gradually took shape. He later recalled that before serving in Washington, he "had experienced fierce tariff battles—yet all these battles were waged at home, arguing whether high or low tariffs were good or bad for the domestic front. Rarely did anyone consider their impact on other nations."

The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act emerged from the ruins of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. While the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act as a protectionist measure triggered retaliatory tariffs by various countries, severely impeding global trade, the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act paved a new path for international cooperation. It introduced three revolutionary concepts that would define the era of reciprocity:

· Executive Power: For nearly 150 years, Congress had carefully guarded its constitutional authority over "the regulation of foreign commerce," resulting in trade policy being influenced by local interests. The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act transferred significant negotiating power to the President, allowing the President to unilaterally reduce tariffs by up to 50% without individual approval from Congress.

· Bilateral Disarmament: This bill allows for targeted negotiations with various trading partners, creating a more strategic approach to trade liberalization and giving the export industry equal footing with the import-competing industry at the negotiating table.

· Most Favored Nation Clause: Any tariff reductions negotiated with any country will automatically apply to all countries that have signed commercial agreements with the United States, creating a multiplier effect that accelerates the global trade liberalization process.

While the bill initially focused on bilateral agreements, it created a template that later served as a reference for the international trade architecture.

1947: The Bretton Woods System and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade - Rules for a World in Flames

As World War II came to an end, the architects of the post-war economic order gathered at a resort hotel in the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The Washington Mountain Hotel in Bretton Woods lent its name to the system they designed - a framework aimed at preventing economic nationalism and financial instability, which were seen as root causes of the war.

The Bretton Woods Conference held in July 1944 brought together 730 representatives from 44 Allied nations for three weeks of intense negotiations. The conference reflected two competing visions for the post-war economic order. On one side was the British economist John Maynard Keynes, representing war-torn Britain, now reliant on U.S. financial aid. On the other side was Harry Dexter White, representing the now dominant U.S. economy.

Keynes put forward an ambitious plan for an "International Clearing Union" that would establish a global currency (which he called "bancor") to automatically balance trade and prevent excessive surpluses or deficits. White's plan was more conservative, preserving national currency sovereignty while establishing a rule of stable exchange rates based on the dollar pegged to gold at $35 per ounce.

White's plan largely prevailed but also made significant concessions to Keynes's concerns about adjustment flexibility. The final agreement established two key institutions: the International Monetary Fund (IMF), tasked with monitoring exchange rates and providing short-term financing to countries facing international balance of payments difficulties; and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, now part of the World Bank), responsible for promoting reconstruction and development through long-term loans.

The Bretton Woods system represented a compromise between the rigidity of the pre-1914 gold standard and the chaotic currency wars of the two world wars. Countries would maintain fixed but adjustable exchange rates to the dollar, with the dollar serving as the system's anchor through its link to gold. The IMF would provide short-term financing to countries facing temporary international payments problems, allowing them to adjust without immediate recourse to austerity policies or competitive currency devaluations.

The design of this system was clear from the start, aiming to prevent the disastrous economic nationalism of the 1930s. By providing liquidity and assistance, the system was intended to give countries breathing room to maintain domestic economic stability and international cooperation. The architects of the Bretton Woods system were keenly aware that the choice between domestic economic objectives and international obligations had torn apart the economic systems of the two world wars. Crucially, the architects of the Bretton Woods system recognized that monetary stability alone was insufficient.

There was a need for a complementary trade framework, as reflected in the signing of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947.

While the United States and the United Kingdom reached agreement within the framework of this system, there were core differences. The U.S. aimed to eliminate the UK's imperial preference system. The UK hoped for significant U.S. tariff reductions, as these tariffs had remained high since the days of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. What was the compromise? Multilateralism, reducing political influence, and dispersing pressure from all sides.

Its core pillars:

· Most Favored Nation (MFN) treatment: Any trade concession made to one member country must apply to all member countries.

· Tariff bindings: Once tariffs are reduced, they cannot be raised freely.

· Quota elimination (in most cases): Because nothing screams "central planning" more than import restrictions on poultry.

Over the following decades, a series of negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) (Annecy, Torquay, Dillon, Kennedy, Tokyo, Uruguay) gradually reduced global tariffs, transforming the post-war temporary peace into a well-functioning world order. By 1994, GATT was renamed the World Trade Organization, and the global average tariff had dropped to below 4% from 22%. Starting with 23 founding contracting parties, it expanded to cover most trading nations in the world and witnessed a sharp expansion of international trade over the post-war decades.

The brilliance of GATT lies in its simplicity. It treated tariffs as nuclear weapons: their use is dangerous, and retaliation is contagious. The core principle of GATT is that not all trade is beneficial, but that any retaliatory protectionism is harmful. In reality, it is a behavioral contract: no more weaponized tariffs. No more trade collapses. If you want to raise barriers, you have to pay the price. If you reach an agreement, you have to share.

It is precisely for this reason that GATT has surprisingly stood the test of time. For decades, it has been effective for a simple reason: when it fails, everyone remembers what happened.

However, it turned out that the Bretton Woods monetary system had weak resilience. Faced with persistent international balance of payments deficits and declining gold reserves, President Nixon suspended the convertibility of the dollar into gold in August 1971, effectively ending the fixed exchange rate Bretton Woods system.

1971: End of US Dollar Gold Convertibility

From the Age of Discovery to the Colonial Era (around 1400 to the mid-1900s), gold and silver served widely as currencies for international trade settlement. In particular, the Spanish silver dollar was most commonly used for international trade settlement (the origin of the term "dollar" is from silver mines). Generally, a fiat currency system based on promissory notes may work well locally (with trust and enforceability), but not internationally.

For example, during the pirate's golden age, the Caribbean was a melting pot for European colonial empires (Great Britain, France, and the Netherlands), all using the Spanish silver dollar for trade settlement. The Spanish Empire was the largest source of silver, minting standardized, ubiquitous silver coins. Even on the other side of the globe, China only accepted silver (especially the Spanish silver dollar) to exchange for the tea it sold to Great Britain.

During the era when the Pound Sterling (backed by gold) was the primary reserve currency, the United States emerged as the world's largest economy during the late 19th-century American Industrial Revolution and became the acknowledged military superpower in 1944. After 1971, the US dollar became the first truly global reserve currency. This can be understood as follows: under winner-takes-all network effects, the dollar became and has remained the dominant global reserve currency.

The impact on the US economy of this shift is not hard to grasp:

Given the global distribution of gold and silver deposits, even under the Bretton Woods system, no single country was the sole source of global reserve assets. Under the Bretton Woods system (1944-1971), currencies were pegged to the dollar, which was exchangeable for gold at a fixed rate. Therefore, in addition to gold itself, the Pound Sterling and the Swiss Franc also acted as functional substitutes for reserve assets.

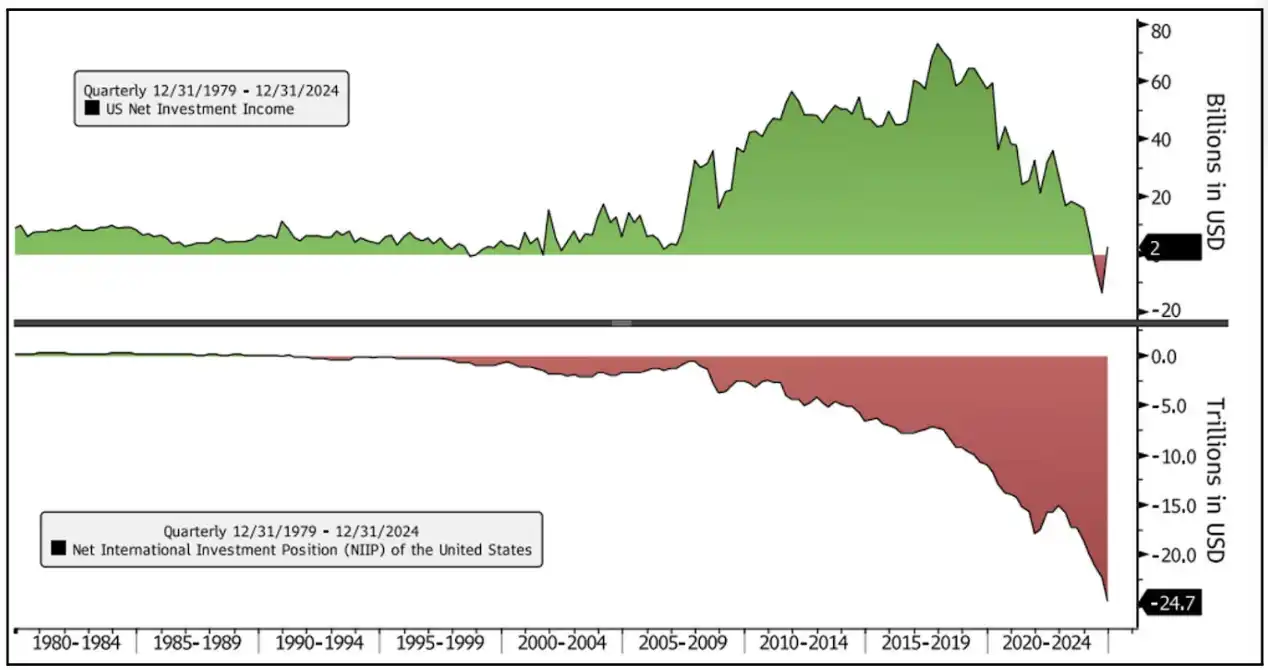

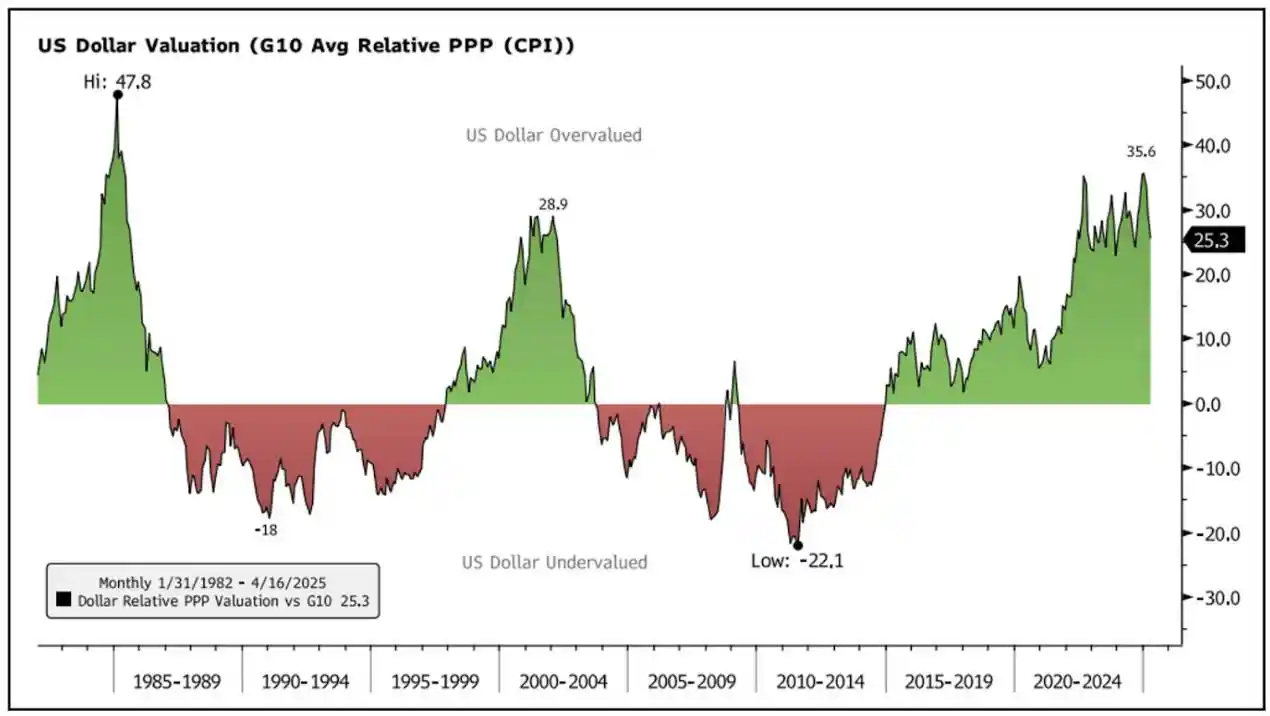

Surprisingly, the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971 actually solidified the dollar's status as the world's reserve currency. As the sole major reserve currency source, the US found itself in a dynamic of persistent trade deficits to provide reserve assets flows to the rest of the world. This seemed paradoxical as initially the dollar was abandoned in favor of something "real" – gold. In the 1980s, Volcker reaffirmed the dollar's status as the world's reserve currency. By 1980, gold was no longer a one-way bet against the dollar. It was "unmasked" as an unstable commodity vulnerable to speculative booms and busts – not a stable store of purchasing power. Since the '80s, the US has struggled to achieve trade surpluses (given the rest of the world's natural tendency to accumulate financial wealth denominated in the reserve currency).

However, the reserve currency status of the US dollar has not been without benefits for the United States. The concept of "exorbitant privilege" implies that even though the rest of the world holds more US assets than the US holds assets abroad, the US actually earns more from its overseas investments. This is because a significant portion of the US's overseas holdings are in the form of high-quality, low-yield US dollar balances and fixed-income securities (such as US Treasury securities, agency MBS, etc.).

When there is international trust and enforcement (which has been the case for decades), a note-based legal tender system can operate globally, but the global order of US hegemony is now being questioned—not by other countries, but by the US itself.

What Does the Future Hold?

While the world has undergone dramatic changes since the post-World War II era of reciprocity, the fundamental contradictions that have shaped US tariff history persist. Today marks a turning point in trade policy akin to those of 1930, 1947, and 1971. Just as those turning points were driven by shifts in the US's global status, today's tariff revival reflects yet another readjustment of economic power. However, a crucial difference between then and now is that the US is actively dismantling a system it helped erect.

This crisis will not end in three months.

Everything the US does in the next three months is not aimed at alleviating the trade burden or returning to a rational mode (e.g., broad tariffs at 10% and targeted reciprocity). This will be the opening salvo. The focus will be on isolating China, attempting to force it to the negotiating table. If you are not with us, you are against us.

The US holds inventory in domestic warehouses equivalent to 2-3 months' worth of supply, enough to offset or distort the initial impact of global trade disruptions. As these inventories deplete, the true effects of a global trade freeze and its repercussions will begin to unfold. Foreign exchange reserve managers will continue to reduce their investments in the dollar as the dollar enters a long bear market.

Suspending additional tariffs is a tactical posture in the ongoing negotiations. The likelihood of a permanent resolution between the US and China in the next 2-3 months is low, but there may be some indirect progress in trade negotiations with European or even Latin American countries. The market will interpret this as a move to ease tensions, but the reality is that it exacerbates the uncertainty in the business environment. To survive the next 90 days, it must be clear...

How to Understand the Government's Perspective?

In this context, understanding the government's perspective would be highly beneficial. In Trump's view, the US hegemony and reserve currency status represent unfair treatment for the US—losing its advantage not only in trade and manufacturing but also in the "free" maintenance of the global trading system. Therefore, the current US position can be roughly summarized as:

What is truly peculiar is not the use of tariffs, as there is nothing peculiar about that. Trump has been a tariff enthusiast for decades, so if you are surprised by tariffs being imposed by the "Tariff Man," you'd better look for another surprise.

Surprisingly, the return of these three "Rs" simultaneously has still not fully unfolded.

· Revenue, appearing in the form of billions of new federal revenue, although not labeled as a tax increase, is essentially no different from a tax increase.

· Restraint, which is not only an industrial strategy but also a populist aesthetics—a wall erected at ports rather than borders, applicable to everything.

· Reciprocity, shifting from mutual barrier relaxation to a feud based on calculating trade imbalances.

Moreover, other factors are at play; this is not simply a revenue issue but one unique to this practice occurring in a globalized world. It requires adding another "R" to define the change represented by such a seemingly straightforward tariff rate hike. Because we are not really reverting to past dynamics but entering an entirely new situation.

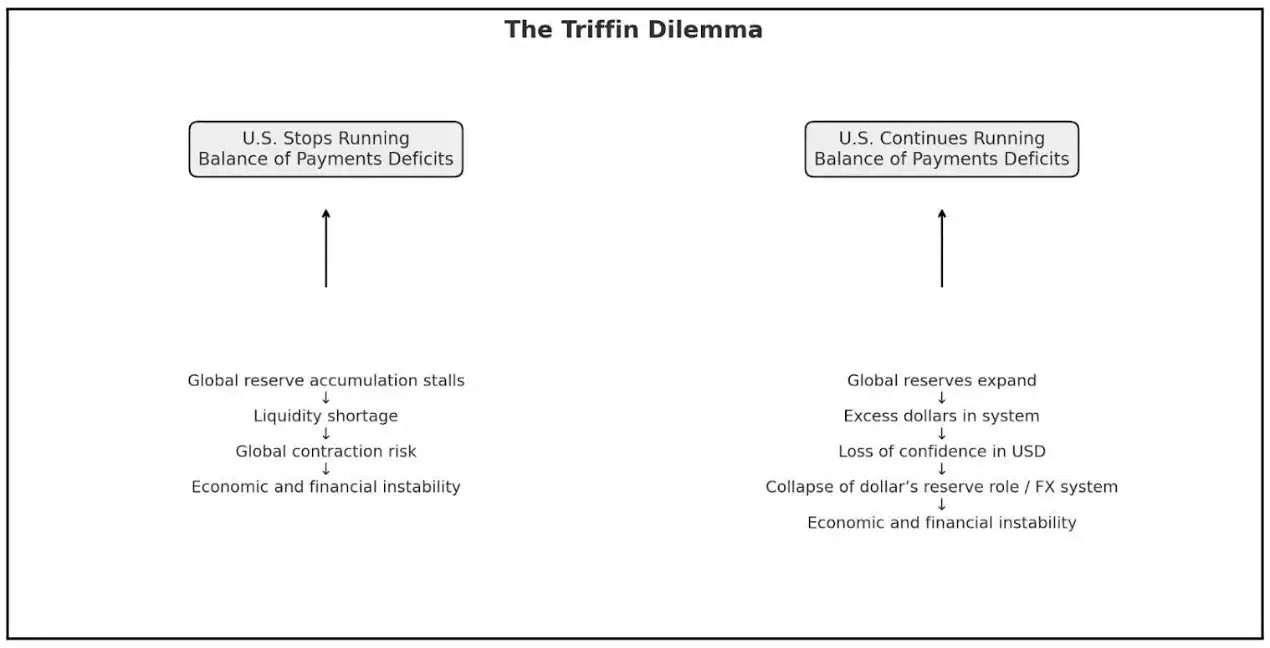

To achieve this, a thorough understanding of the government's viewpoint is necessary. In our article "Seeing the Stag" from two weeks ago, we mentioned the challenges faced in attempting to rebalance global trade by targeting other countries' deficits. The "Triffin Dilemma" describes a dilemma faced by a reserve currency country (which had emerged before the end of the US dollar's gold convertibility). This dilemma is as follows:

"To supply the whole world with reserve and redemption services is difficult for one country and one currency to bear." - Henry H. Fowler (US Secretary of the Treasury)

As expected, the Trump administration's interpretation of the "Triffin Dilemma" is more like a bill rather than an IMF white paper. They believe the US has been exploited, forced to bear the external trade surplus, and they want to correct this phenomenon. By imposing tariffs on countries with trade deficits, they have effectively demonstrated their priorities and concerns.

From the Trump administration's perspective, what is happening/has happened in the existing system is:

· Foreign central banks purchase US dollars not out of preference but out of obligation—because if you want to lower your currency exchange rate and increase exports, you need to hoard dollars.

· Those dollars that went into US Treasuries, in fact, provided the very funds for the same US government that complains about being taken advantage of.

· The dollar remains in a structurally overvalued state, a direct result of the dollar serving as everyone else's savings account and life raft.

· US manufacturing has been hollowed out not because of cheating by China but because the US plays the role of the system administrator in a network it does not fully control.

Ultimately, the trade deficit continues to widen, a term President Trump dislikes, as well as the idea of being the world's largest "debtor nation." The reserve currency role is starting to be seen as a liability rather than a privilege.

From this perspective, tariffs are not just about protecting factories or funding the government. They are overdue fees for system maintenance. In fact, they are like the geopolitical version of "rent," equivalent to forgetting you subscribed but still having to pay $14.99 every month. Simply put, the government's view is: "We manage this system—regulate traffic, ensure channel security, buy your export products, issue your reserve assets. And now we're going to charge you for it."

The Fourth R: Rent

Rent redefines tariffs as a fee-for-service model of global economic participation, rather than a means of providing revenue to a nation, protecting domestic producers, or ensuring reciprocal access. This new mode essentially...

Globalization as a Service

Tariffs, NATO threats, opposition to foreign acquisitions, etc., are forming a deliberate pattern: using all available means to siphon national wealth from foreign client states. Even if this means undermining global trade and the dollar's reserve asset status.

Tariffs are a blunt tool, which Trump clearly is using as part of a broader negotiation, attempting to subvert this system. The 125% tariff rate on China is the most obvious example. Such high tariffs would lead to trade disruptions. So, why not use sanctions or quotas? Because opening negotiations from a "paying fee" angle is crucial.

The 90-day tariff truce negotiations could lead to various outcomes. The primary focus will be on forming an alliance to force China to the negotiating table, but discussions on how to levy this "fee" in a more enduring manner may also begin.

How Is Rent Paid?

I have always been skeptical of the idea of the "Mar-a-Lago Accord" and find it highly improbable. However, the discussion is still valuable. The proposed issuance of hundred-year bonds could have unintended negative consequences but illustrates well how the fourth "R" (Rent) operates. The idea is: by issuing hundred-year bonds with a negative real interest rate and encouraging (forcing) nations to swap their existing long-term bonds for newly issued bonds, the US can derive additional economic benefits from maintaining its world reserve currency status and global trade promoter status.

Despite its unpredictable and potentially disruptive nature that could damage the reputation of the United States and severely distort the yield curve, Trump might be eager to waive tariffs (or significantly reduce tariffs) for countries agreeing to convert their government debt to hundred-year bonds with a negative real interest rate. After all, he has spent a lifetime restructuring and refinancing debt for various Trump-owned entities.

This is just one example, and a rather unlikely one. Stephen Moore recently stated that he does not endorse this idea. However, the fact remains that Trump is challenging the existing international rules of the game and questioning the role of the US dollar and US government debt. Why? Because he is solely focused on the current impact on US finances. This viewpoint carries a risk of missing the bigger picture.

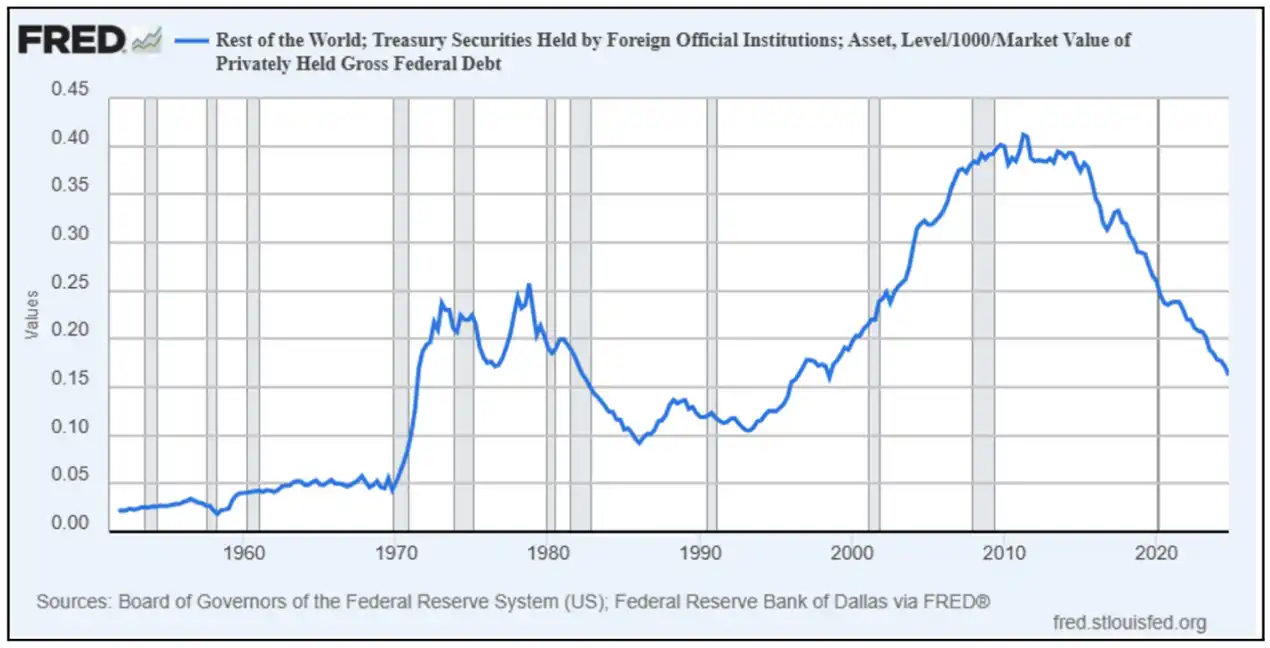

If the US were to effectively default on foreign-held government debt in a hostile century bond issuance/swap, it could lead to a rise in gold prices and a decline in the US dollar. The impact on the yield curve would be significant. Even if such a scenario does not unfold, official foreign exchange reserve assets seem poised to further diversify towards gold, the euro, the franc, and the yen. Additionally, agreements for trade settlement in currencies other than the US dollar could be reached.

Faced with this potential reality, it is not surprising that official holdings of US government debt by other countries have been declining for years:

The current US policy is easily viewed by other countries as economic extortion. This high-risk economic brinkmanship policy itself is extremely risky. If it fails, it is akin to the US being both the bank and the client, taking out a loan from the bank... and then deciding to default on its own. But the reality remains: countries are still negotiating with someone ready to dismantle the entire system at any moment, regardless of the consequences. It is not difficult to see how many countries would prefer to submit rather than face a de-globalized world and predicament.

Will this situation have outcomes that will not seriously harm the global economy? Yes, but it will not lead to a swift restoration of global trust in the US. Regardless of how the negotiations unfold, it is apparent that trade policy will be a key driver of cross-asset returns and economic growth this year. Clearly, we are witnessing an institutional shift that will have implications for the macroeconomy in the years to come.

In this new regime, tariffs are more of a precedent than a policy. The US has shown that it will use market access as a lever, tightening or loosening trade conditions based on geopolitical compliance rather than economic efficiency. Whether the government proposes large-scale tax cuts or other supportive measures will ultimately depend on the pace and manner of progress in US-China trade negotiations.

There is nothing more crucial than this right now. The US and China have already rapidly experienced a spiraling escalation of retaliation under the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, reaching as high as 145%.

Therefore, even though the circumstances and environment are vastly different, it is not difficult to understand how those desperate economists and bankers in 1930 felt when witnessing the outbreak of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act trade war. Globalization has become somewhat like economic mutually assured destruction. There may be "winners." Perhaps one country is only destroyed 80%, while the others are completely wiped out. But is this really the world we expect?

Unlike the Hoover administration, the Trump administration faces the contradiction of being both a debtor nation and a trade-restrictive nation. Although both disregarded economists' warnings and attempted to maintain America's position through tariffs, Hoover's policy was primarily a defensive (and misguided) measure taken to protect American industry, whereas today's approach includes an additional offensive element: intentionally using America's debtor nation status as leverage to transform the global trade and financial system from a public good into a privately tolled highway.

While it might be tempting to look back to the last time tariffs were this high and say, "Well, maybe this could happen again," there are issues with doing so.

Return of Tariff Nations?

Today is not the 1890s or the 1930s. Today's world is already globalized, integrated, and has never attempted re-separation.

We are not far from an event that will make us deeply realize how interconnected the world has become. The pandemic has not only caused destruction but has also revealed truths. It has vividly shown us how fragile the global trade architecture has become. Ships are stranded, semiconductors are missing, and the illusion of a robust supply chain has shattered.

I don't think we can just... dismantle the supply chain. I also don't think the U.S. can escape the just-in-time, on-site, and barely resilient systems that have been designed over decades through tariff imposition. Trump's trade policy is not the Smoot-Hawley Act, although many have tried to draw parallels.

I don't think we can... easily unravel the supply chain. I also don't think the U.S. can get rid of systems designed for decades to be just-in-time, on-site, and almost entirely inflexible through tariffs. Despite many attempts to compare it to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, Trump's trade policy is not the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act. The most unsettling thing is that there is no historical reference frame. You can draw on events from the 1970s, 1930s, and any other reshaping of the underlying system architecture, but that does not explain all the issues.

In the 1930s, the world did not see a phenomenon of deglobalization because the level of globalization was still low at that time. Today, for the first time, we are witnessing a superpower actively sticking a stick into the spoke of globalization it helped build.

The key is: It might work. Just temporarily, politically. Until it doesn't. Like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act that was in effect for about three months—until Canada retaliated, Europe raised tariffs again, and global trade descended into a trap. While the number of bankrupted American farmers hit a record high, they still voted for those who depressed the prices of their agricultural products.

Today's tariffs may take a different form, but functionally they are no different. They are all based on the same belief: that stability can be achieved by disrupting complexity. Unfortunately, complexity does not yield easily.

To be frank, no one fully understands how our complex and ever-changing global system operates in real-time. Not the Fed, not CEOs, not the IMF, and certainly not you and me. The cascading effects are simply incomprehensible. Yet, if we continue on this current trajectory, our collective understanding of it seems poised to increase only in the most unsettling ways.

This raises a straightforward question:

· In a world where rules can change next quarter, how can a company commit to a 30-year, capital-intensive investment?

· In an atmosphere where tariffs are not policy but subject to the next tweet, the next election, the next wave of populism?

This is not just a trade issue, it's a capital formation issue. Long-term investment can only exist under an extremely rare combination of circumstances: predictability and trust in institutions are among the most crucial factors.

Although the U.S. market has shown remarkable resilience through world wars, the Great Depression, stagflation, the dot-com bubble, and bank runs, this resilience is not incidental. It is built on a composition of rare and volatile ingredients that most countries cannot piece together, let alone sustain for decades.

First is global trade. For nearly a century, the U.S. has been the central node in the world's commercial network—not because it produces the cheapest goods, but because it offers the deepest market, the most trusted currency, and the broadest consumer base. Trade has been the unsung hero of America's prosperity, allowing the U.S. to import low-cost goods, export high-value services, and turn global surpluses into domestic assets.

Second is political stability. Regardless of how people view the polarization of the two-party system and all its absurdities, the peaceful transfer of power every four years and the continuity of contracts, courts, and governance make capital confident to stay. Investors may dislike regulations, but they dislike chaos even more.

Add to that a sound set of legal and regulatory frameworks. Property rights system. Bankruptcy courts. Enforceable contracts. These are the mundane technical architectures of capitalism, but without them, capital cannot flow.

Of course, there is also the dollar. The U.S. dollar's status as a global reserve currency has created a gravitational field for global capital. Foreign central banks, sovereign wealth funds, multinational corporations: they all hold dollar reserves, settle transactions in dollars, and manage risk in dollars. This demand lowers America's borrowing costs and gives it an unparalleled ability to sustain deficits without immediate consequences.

Lastly, there is luck. Two vast oceans, intersecting rivers and navigable waterways, natural harbors, uniquely favorable agricultural conditions, and a century and a half without hostile neighbors. Abundant natural resources. A booming population at critical times. A continental-sized domestic market. If one were to design a nation destined for dominance, the map of America would be the ideal blueprint. It can be said that America is quite fortunate.

While this system may seem stable on the surface, it is actually intricate, interdependent—sustained by the inevitability of geopolitics, norms, incentives, and a polite collective delusion that tomorrow will roughly resemble today. Only major geopolitical events that reshape the system's architecture lead to long-term disruptions, without moments of "buying the dip"—1971 is a classic example.

Returning to the fundamental question, an answer to this question will soon be found. What is the cost of unpredictability?

What is the cost of unpredictability? To be honest, I don't know. I believe no one knows. The limit to what this system can bear is finite, and once crossed, it cannot be reversed. Perhaps the good news is that the United States still wields more influence than any other country in the world. However, unless other nations come together or are willing to endure more pain than the Trump administration anticipated.

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

Justin Sun Highlights the Promising Future of JST Token Through JustLend

In Brief Justin Sun sees great potential for JST tokens through JustLend's growth. Buyback and token burn strategies aim to enhance JST's market value. Investors are advised to analyze TRON's evolving landscape cautiously.

The Melania team used a fixed investment strategy to sell 3.19 million MELANIA

Matrixport: New capital inflows indicate that Bitcoin is expected to break through $100,000

Bitcoin's 10% Surge Sparks Optimism for SUI, AVAX, TRUMP, and TAO